Hey guys, have you ever wondered how a code line turns into electricity? Let’s talk about it as far as I know and also the trending topic AI knows 😀

My example will be focusing on embedded development today. However, the principle is almost the same anywhere.

We write if (button_pressed), and a light turns on. It feels like magic, but between our keyboard and the silicon chip, a massive industrial process takes place: Build System. Let’s break down the journey of our code using a simple analogy: The Professional Kitchen.

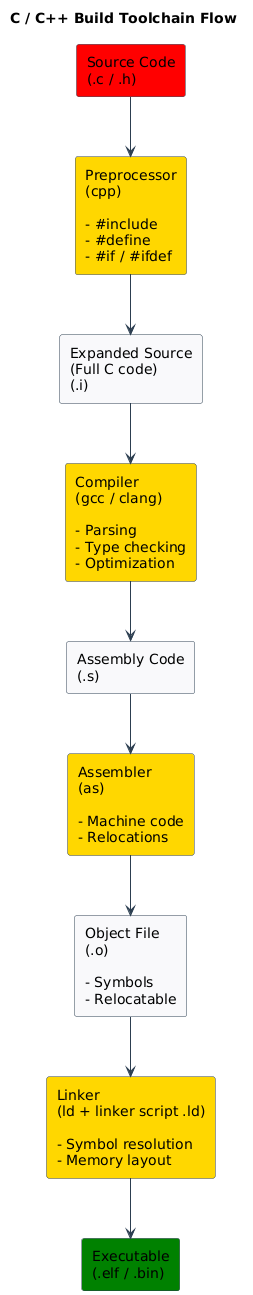

Before we start, here is the simplified diagram:

1. The Inputs: The Recipes

Our project starts with text files.

- Source (

.c,.cpp): These are our main recipes. They contain the instructions. - Headers (

.h): These are the ingredient lists. They define what’s available to use.

But our microcontroller (the customer) doesn’t speak English (C/C++ code). It only eats binary. We need a staff to prepare the meal.

2. The Preprocessor: The Prep Cook

Before any real cooking happens, the Preprocessor steps in.

- The Job: It handles everything starting with

#. It takes our#include "file.h"and physically copies that text into the source file. It replaces macros (#define). - The Result: A massive, expanded text file with all ingredients gathered in one pile.

3. The Compiler: The Translator Chef

Now, the Compiler (gcc) enters. This is the brain of the operation.

- The Job: It reads the C code and translates it into Assembly (

.s). - The Result: We have moved from human language to architecture-specific instructions (like

MOV,ADD,LDR). The recipe is now written in the “alien language” of our specific chip.

4. The Assembler: The Robot

The Assembler (as) is purely mechanical.

- The Job: It takes those assembly instructions and converts them 1:1 into machine code (binary zeros and ones).

- The Result: An Object File (

.o). - Important: Think of this as a cooked steak sitting in a pan. It is “done,” but it doesn’t have a plate yet. It doesn’t know where it belongs in the final meal.

5. The Linker: The Plating Expert

This is the most critical step in embedded systems. The Linker (ld) combines all our object files (main.o, display.o, drivers.o) into one final executable.

On a desktop computer, the operating system decides where to put code in memory. In an embedded system, you decide. The Linker Script is the “Plating Guide.” It tells the linker:

“Put the code instructions in Flash Memory (start address 0x0800…), but put the variables in RAM (start address 0x2000…).”

Without the linker script, our code is just a pile of food with nowhere to sit.

The Final Course: The Executable

Once linked, we get an ELF file (.elf). This contains the code plus debug info (like nutritional facts).

For the actual chip, we usually strip it down to a BIN (.bin) or HEX (.hex) file. This is pure machine code—the final meal served directly to the microcontroller’s memory.

Summary

Next time you click “Build,” remember the journey:

- Preprocess: Gather ingredients.

- Compile: Translate to Assembly.

- Assemble: Convert to Machine Code (Object files).

- Link: Map specific code to specific memory addresses.

Happy programming!

Leave a Reply